Raising boys

Boys have traditionally been discouraged from showing their feelings, with often damaging results. So an unusual Scout Group – all boys – broke with convention to help promote wellbeing in their community.

The Scouts is an inclusive movement of young people, proudly open to all – boys, girls, LGBTQ+ young people, everyone. 9th North Leeds Scout Group is therefore a rarity: a Group made up entirely of boys. And so, when they took on the challenge to explore mental wellbeing for A Million Hands, the mental wellbeing of boys naturally came into focus. As it turns out, they’re not the only ones tackling the topic.

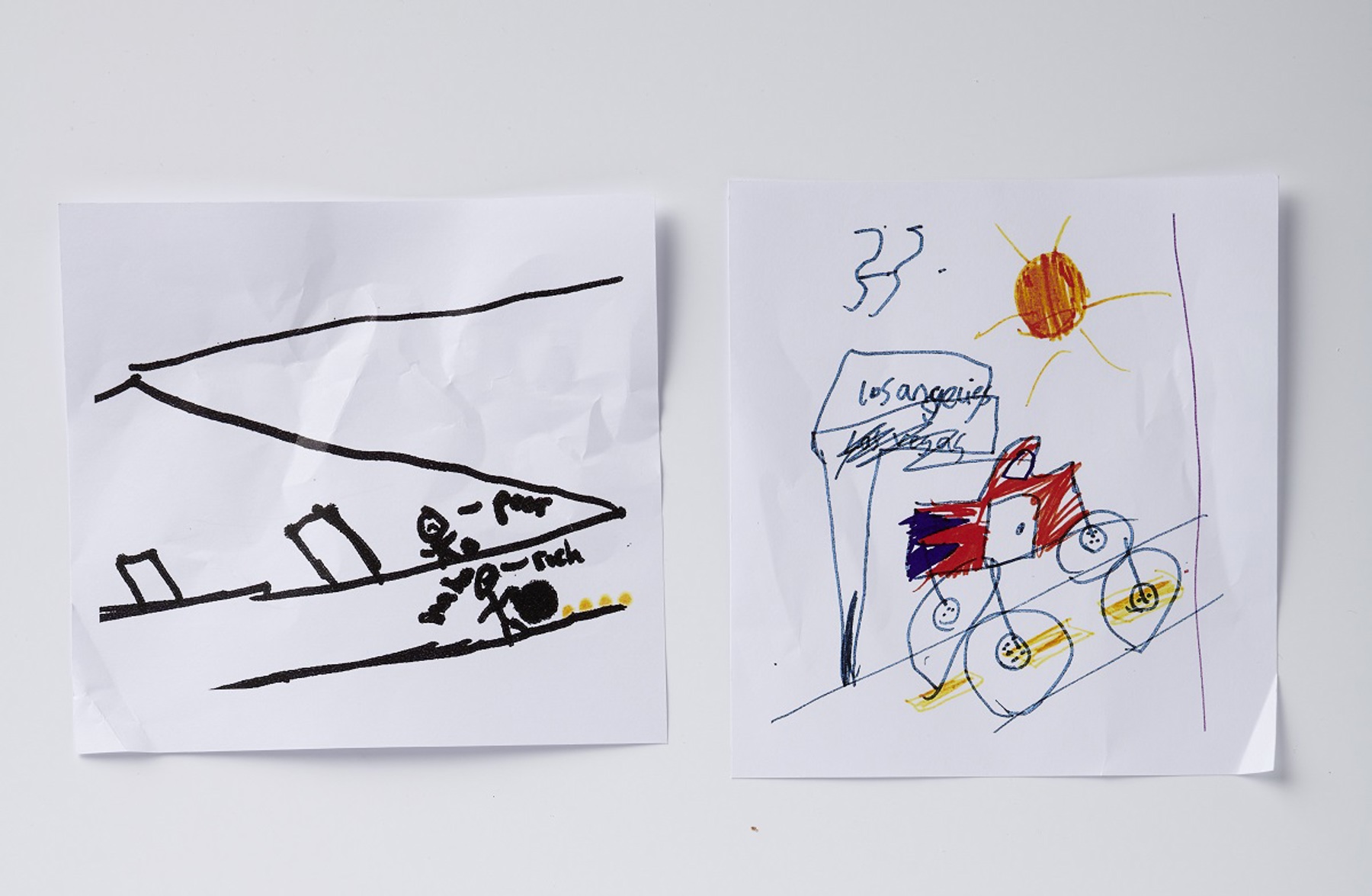

To illustrate a petition sent to their local MP, the boys drew two things: what makes them feel happy and what makes them feel sad. One drew a picture of a figure crooked with anxiety; another a little boy scoring a goal with glee; one scribbled ‘when my dog died I felt like the world was empty’. Paging through the pictures, the message behind the petition shines bright – in short: the way people feel matters.

Signed by 72 Scouts plus 62 members of their community, the petition asked their MP what steps are being taken to ensure the equity of access to treatment of physical and mental health services in England – and to reduce the incidence of suicide.

Reflecting on a few things that had happened in their community, choosing mental health as their social impact issue seemed like an appropriate choice. When the Group took on the challenge in late 2015, Assistant Scout Leader David Donaldson says they began very simply. Sometimes it was just a case of recognising that we all have feelings, and then working through the resources developed by mental health charity MIND to explore mental wellbeing – ‘essentially, what makes us feel happy and what makes us feel sad,’ he says – and how with self-awareness we can help manage and strengthen our mental resilience, just as we learn to look after our physical health.

It’s OK to talk about this stuff. When I was a Cub, 60 years ago, no, you didn’t talk about your feelings.

David Donaldson, Assistant Scout Leader

In the leafy suburb where the Group is based, Assistant Scout Leader Andy Smith reflects on the impact of the challenge: ‘I’ve been thinking about it recently – what has it done? Has it changed anything? And I don’t know. There was an openness from the young people, but maybe it’s made us spot that they are more open to saying, “I’m a bit scared of that”, on camp or something. They’ll be honest about it. Whereas maybe our generation were more…’ he whispers: ‘“Oh no, I can’t tell anyone about that… just get on with it.” But whether that’s changed or that’s us noticing it through the mental health activities we’ve done with them, I’m not 100% sure.’

‘I’d agree with that,’ says David, ‘it could be the leaders as much as the lads. That it’s OK to talk about this stuff. When I was a Cub, 60 years ago, no, you didn’t talk about your feelings. It was “soft”, it was inappropriate.

A silent suppression

With young men more likely to die by suicide than by any other cause of death, the question of how to support men’s mental health has gained traction in recent years. The reasons behind the high incidence of male suicide are highly complex, but studies show contributing factors include relationship breakdown, unemployment, bereavement and mental health problems. Dr Ben Hine – senior lecturer in psychology at the University of West London and co-founder of the Men and Boys Coalition – says ‘there are multiple risk factors at play. Our understanding of the relationship between sex, gender and suicide is still in its infancy, and some of the arguments made regarding men’s high suicide rate are therefore a little simplistic; for example, the argument that because men don’t express their emotions that means when they have problems they commit suicide.

‘That being said, masculine norms and expectations certainly don’t help, as men are socialised away from showing vulnerability and weakness and sharing their emotions with others. They are also discouraged from the kind of close, personal, emotionally open relationships expected of women, which means they may be less likely

to share with friends or family when confronted with serious issues. Add to this the fact that most services are designed around a ‘female’ model of sharing and communication, and that there is a stigma particularly around men’s mental health, and it is no wonder that men may feel that they have no other option.’ As one Scout put it, ‘If you can’t speak about a feeling it gets locked inside and it builds up, like tension, the more you keep it inside.’

More and more people are questioning the expectations of certain forms of masculinity. Last year, comedian Robert Webb’s memoir How Not To Be A Boy shot to the top of the charts. In it he examines the potential damage of encouraging young boys to follow the supposed ‘rules’ of their gender, when these aren’t suited to everyone. Growing up, Webb thought that to be a ‘real man’ he needed to get into fights, obsess over sport, never cry and not talk about feelings. It was a box he didn’t fit into and it led to destructive consequences.

Among the countless reports on the topic, the documentary The Mask You Live In interrogates versions of masculinity that box men into a role in which they’re expected to suppress any sign of weakness. Expressions such as ‘real men don’t cry’ or ‘man up’, which imply that men should be strong at all times, can put pressure on men to conceal the more vulnerable sides of themselves. In 2015, The Telegraph posed the question: ‘Is ‘man up’ the most destructive phrase in modern culture?’ Dr Hine believes, ‘There are few more damaging phrases that exist in the English language. Whenever it is used, in whatever context, it reinforces the idea that to be manly is to be strong, and to suppress emotional expression.’

The phrase is not only damaging to women, he explains, ‘as it suggests that men have the monopoly on the characteristic of strength’, but it also, ‘continuously and insidiously reinforces to men that they, fundamentally, as men, must be strong and not show weakness or vulnerability of any kind. This leaves them in an extremely vulnerable position (ironically) as it does not allow for the healthy sharing and expression of emotion that is

needed for good mental and physical health.’

David also hates the expression. ‘It has all sorts of connotations. I didn’t really get to grips with this, and with my own feelings, until about 10 or 12 years ago and that was because I was ill with depression and I learned a whole new language and learned how to talk about it.

‘So it’s good to see that this generation is willing to talk about it and recognises that your wellbeing and your feelings are just as important as the strength of your arm and your ability to climb a tree.’

From boys to men

The boys in the Group talk about their feelings willingly, but in some cases the older the boys are, the less open they seem. Dr Hine reflects on this, what he describes as the ‘emotional spectrum that we gradually shrink for boys as they grow’, explaining that, ‘even boys as young as eight have trouble with providing words to describe their emotions, other than anger – the principal emotion that we reserve for boys, and the men they become. This fits into a bigger picture of an incredibly restrictive and damaging male gender role that boys are still socialised into.

Author Tim Winton, whose novels often explore the damage caused by this traditional image of masculinity, says, ‘It’s almost as though kids show up with a box of coloured pencils in infancy and as a little boy you’re allowed to do a lot of things. You’re allowed to do almost anything, up to a certain age, and then they start taking the pencils off you. They take yellow and red and orange off you. By the time you’re 11, you’re down to the blacks and the blues and the purples and by the time you’re 17, it’s all the dark colours – you’re not allowed to do certain things. You can’t kiss your father good-bye, you wouldn’t hold another boy’s hand. You couldn’t express any softness. All the things that are actually part of being a boy and which we associate with exclusive feminine traits, they’re boys’ as well, they just get robbed of them.’

The extent to which masculine and feminine traits are innate or socialised into us is at the centre of gender research. In Dr Hine’s view, based on the current research available, ‘whilst there are fundamental biological elements that differentiate men and women, much of the behaviour we deem as typical or appropriate for men and women, and our concepts of masculinity and femininity, is at least in part socially constructed (I would say mostly)… In infancy our neurobiology is moulded by the environment to a greater extent than any other mammal.’

Because this nature-nurture debate is an issue of ongoing research, the question of what it means to be a man today can be a contentious, sometimes divisive subject. But it’s one that plays an important role in the formation of individuals’ identities and mental wellbeing, as well as wider social justice. It warrants exploring in pursuit of a society where all people – across the gender spectrum – are empowered without disempowering someone else.

As a movement supporting young people, we need to ensure we are supporting all young people – regardless of their sex or the gender they identify with – to think positively about feminine and masculine traits, so they can engage in the world with confidence, kindness and a deeper sense of resilience. Where being vulnerable, processing the failures that we all face, and breaking down sometimes, can feel like a natural part of life rather than the end of the world.

The talking cure

Talking about the stress balls they’d made, one Beaver says you should squeeze one when you’re angry. ‘Without a stress ball, someone might just react, fight. And I don’t think that’s good. I don’t like fighting,’ he says. You can tell when someone is angry, one Scout explains, because ‘they go quite red’, ‘they react without thought almost. Like they have no filter… so they’re not being the nicest person they can be.’

To make himself feel less angry, one Scout tells us, ‘I just think happy thoughts,’ before another quips, ‘Yeah, I think about anything but my sister.’

The young people explain that it’s not always easy to talk about feelings. ‘If it’s happiness, you can go bursting out, like, “Hi it’s my birthday, it’s my birthday!”’ says one, ‘But if it’s something you’re sad about, it’s quite hard and you just keep it to yourself. Like if you’ve lost a member of the family maybe, or if your parents split up, things like that.’ One Beaver says when he’s feeling really sad he hides under his bed, explaining: ‘I just go to the bottom of it and then I just calm down.

For many people, regardless of gender, talking about difficult feelings can be a challenge, but Dr Hine believes, ‘When it comes to men and mental health, one of the principle misconceptions is that men aren’t talking or that they don’t want to talk. It is much more useful to say that we tell them not to talk, that we aren’t listening, and that we aren’t listening in a way that makes men feel comfortable sharing. For example, some of the most successful men’s mental health initiatives acknowledge that men prefer to discuss their feelings whilst engaged in a joint activity with their listener.’

Considering the research linking Scouts to mental health, perhaps there’s something to this, as being a Scout offers opportunities to connect with others in an activity-based format. Andy says the A Million Hands mental health challenge has influenced the activities they do with the young people – how they build their resilience. A few weeks earlier, the Scout section had gone on a camp they called Survival Night. There was this hum of: ‘We’ve got to survive… we’ve got to get through,’ Andy remembers.

The Scouts had to build their own shelters and then a thunderstorm arrived and the rain just poured in. ‘Sleeping bags were soaked and suddenly there was this chorus of “I want to go home”… But they stayed and, you know, another sleeping bag arrived and a tent went up rather than a washed-out shelter and they spoke about their feelings and in the morning it was like: “I survived!”

Some of the most successful men’s mental health initiatives acknowledge that men prefer to discuss their feelings whilst engaged in a joint activity with their listener.

Dr Ben Hine

Safe spaces

Creating an environment that nurtures mental wellbeing isn’t about being prescriptive when it comes to talking about feelings, says David. ‘It’s more about an attitude in the room. The way people interact, the way we’re willing as leaders to have them interact. We won’t have bullying and we won’t have racism and we won’t have all sorts of things, but we try not to be too rule-based and just talk about being kind to one another. ‘We ask “how do we deal with this situation, how do we be inclusive and encourage all people?” It’s not just about listening and talking about the woes and miseries and being able to talk about them. There are things we can do to look after ourselves – connecting with people, being active, taking notice when things are not going right.’

Andy says he doesn’t know if the young people were ‘necessarily making that link between being happy or sad and anxiety and depression. But they were quite open to talking about it and I think hopefully that’s one of the things that carries forward and makes the difference. That we’ve got a generation of young people coming through who are more open to talking about their feelings – and sooner.’