Approaching tasks and problems

(FS310600)

Frequently in our lives, whether at home, work, or in Scouting, we find ourselves with an enormous job to do or problem to solve.

Many times, we feel unable to even think about tackling it, let alone completing it successfully, but using diagrams in these situations is something that many people find helpful.

Using diagrams to help in these situations is something that many people find very useful. There are two common occasions to use diagrams:

1. When facing a task

2. When facing a problem

On the face of it, these seem as if they are the same thing, but it's important to understand the differences.

Tasks

Simply put, a task is “something you need to do”, for example, build a garden shed. It's not necessarily urgent, but it is something that needs doing because if left outside the lawnmower will eventually go rusty.

Using a diagram in this situation will give you a greater understanding of the task, and help you identify all the actions that are needed to complete the task, and so break it down into more manageable pieces.

Problems

A problem is more urgent, “something you need to solve soon”. This could actually be a task that has been left undone for so long that it has become a problem. For example, you might go outside to cut the grass one morning and the lawnmower blade jams because it has gone rusty. If you had built the garden shed, a year ago like you had meant to, then the lawnmower wouldn’t be rusty.

Using a diagram here helps you to look more closely at the problem and gain a greater understanding of it. It also helps you to identify all the possible causes of the problem, and so stops you from jumping to wrong conclusions.

Approaching tasks and problems

- It's easier to approach pieces of the job than the whole of it in one go.

- Decisions need to be based on the BEST information – diagrams help to identify information that is needed.

- Diagrams can help you use your time more efficiently.

It's important to remember that many issues can be approached in different ways, either as a problem to solve or a task to complete. How you approach each situation is likely to depend on the circumstances that surround it. It could be a long-term project (in which case this is likely to be approached as a task), or it could be an emergency response to a serious situation, which you would probably treat as a problem.

The following four diagrams are examples you could use to approach a task or problem.

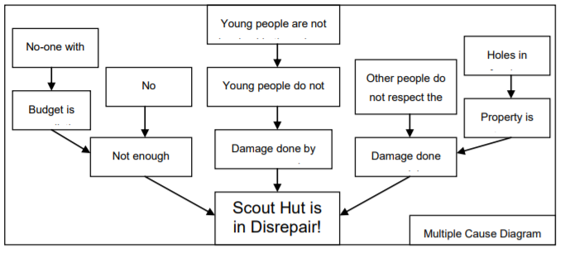

The multiple cause diagram is based around the idea that any problem or task has a number of causes that could make it happen.

How to use it

Begin by deciding what problem you wish to solve, or what you wish to achieve, and write this in the box at the bottom of the page.

The task / problem can be as vague as is necessary, i.e. the diagram on page one could have the main problem as “The Scout Group isn’t Meeting!”, because the Scout Hut is in disrepair.

Next, identify all the possible reasons for the problem, or key actions that will contribute to the task i.e. Not enough money, damage etc. The process of identifying causes continues until no more can be thought of.

Useful, because

- Its very clear and easy to understand.

- Can be quickly drawn up.

- Its best use is for discovering the causes of problems and breaking them down into easier segments to deal with.

But, remember

Some causes lead to many problems, which may make the diagram more difficult to construct.

It's easy to miss some possible causes because there is no guidance over which areas to cover.

This diagram does not point obviously towards a solution, but rather helps to break down the whole into smaller, more manageable “causes”. There are various methods suggested for finding solutions, and most of them involve a process of:

1. discovering the facts,

2. clarifying the problem,

3. brainstorming for possible solutions,

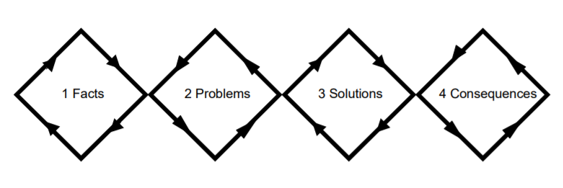

4. discussing the implications of carrying them out, as is described in “Diagram 2 – Diamonds”.

How to use it

Establish all the facts you need to approach the problem, i.e. people, places, events, and the time scale. It is essential that this stage is completed thoroughly, because without all the information, the chosen solution will not correctly address the situation.

Now that you have gathered the facts, make sure you fully understand the problem. To do this, look objectively at the situation (sometimes writing this down may help). You may find that you don’t have all the information you need, if this is the case, go back and look at the facts again. Remember to ask yourself if what you are looking at is the REAL problem.

Once you are certain you have all the facts and understand the problem, think of as many different solutions as you can, however bizarre. Sometimes the strangest ideas lead to the ones that work!

Remember that postponing the decision or doing nothing are also options to consider. Check these solutions against the problem and the facts to see if they are relevant to the problem.

After eliminating any invalid solutions, go through what’s left and predict what the consequences of carrying out each solution would be. If the solution creates more problems than it solves, then it really achieves very little. Remember also that people do not always react in a logical manner, so this must be allowed for. Once you have found the “best” solution, put it into action!

Useful, because

- It takes you systematically through the problem.

- It helps you to use your time more efficiently.

But, remember

- It's not suitable for tasks.

- It does not really encourage writing down, so visualising the situation can be more difficult.

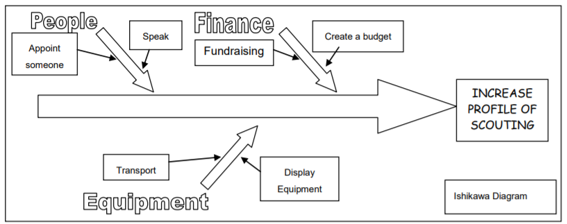

How to use it

This diagram is most useful for approaching a task, so write the task you are working on in a box at the right hand of your page.

Draw an arrow across the sheet, pointing towards the box; and then add further arrows connecting to the sides of this main arrow. – Each side arrow represents a group of causes that will lead to the completion of the task such as: People, Equipment, Method, Materials or Finances.

Around these side arrows, arrange the various activities that need to be done in that area. When drawn with care and forethought, this diagram will give a comprehensive list of all the causes that will lead to the completion of the task.

Useful, because

- It gives a good indication/guidance over which areas to think about.

- It can stop you jumping to the wrong conclusions.

But, remember

- It can be easy to miss some causes.

- This may get confusing with a large project

- It is not really appropriate for problems.

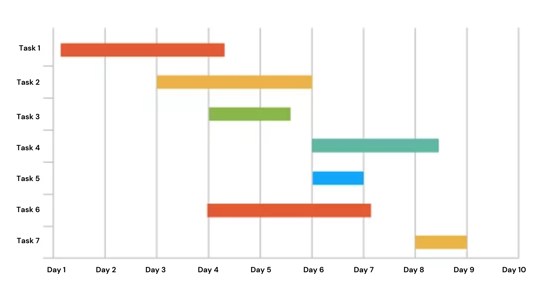

How to use it

The Gantt chart turns a “shopping list” of activities to be done into a graph showing when the tasks will be done, and by whom.

Begin by listing all the activities that need to take place in order to achieve the end goal (in this example, organising a Group Jumble Sale). Group related tasks together and include who is going to be responsible for each task, or group of tasks.

Next, mark out the time period across the top of the graph (in appropriate intervals). Add boxes to the diagram showing the period of time during which each task will be completed.

To enable you to report progress, draw the boxes hollow to begin with and then fill them in when the task is complete. For example, in the diagram below, all those involved are still selling jumble and the Treasurer & Chairman are still counting profits.

All this can be done using computer software, which is extremely helpful for very large projects that are likely to change regularly, however for smaller projects this diagram can be constructed by hand.

Useful, because

- It's easy to understand.

- It's easy to produce.

But, remember

- Its best use is for medium or small projects with a team of a dozen or so.

- You need to make sure you don’t assign more tasks to one person than they are physically able to do.

- It can be difficult with large projects to see which tasks rely on others.

- It is difficult to apply this to solving problems, rather than tasks.